Permissions

The Unix-like operating systems, such as Linux differ from other computing systems in that they are not only multitasking but also multi-user.

What exactly does this mean? It means that more than one user can be

operating the computer at the same time. While a desktop or laptop computer

only has one keyboard and monitor, it can still be used by more than one user.

For example, if the computer is attached to a network, or the Internet, remote

users can log in via ssh (secure shell) and operate the

computer. In fact, remote users can execute graphical applications and have the

output displayed on a remote computer. The X Window system supports this.

The multi-user capability of Unix-like systems is a feature that is deeply ingrained into the design of the operating system. If we remember the environment in which Unix was created, this makes perfect sense. Years ago before computers were "personal," they were large, expensive, and centralized. A typical university computer system consisted of a large mainframe computer located in some building on campus and terminals were located throughout the campus, each connected to the large central computer. The computer would support many users at the same time.

In order to make this practical, a method had to be devised to protect the users from each other. After all, we wouldn't want the actions of one user to crash the computer, nor would we allow one user to interfere with the files belonging to another user.

This lesson will cover the following commands:

chmod- modify file access rightssu- temporarily become the superusersudo- temporarily become the superuserchown- change file ownershipchgrp- change a file's group ownership

File Permissions

On a Linux system, each file and directory is assigned access rights for the owner of the file, the members of a group of related users, and everybody else. Rights can be assigned to read a file, to write a file, and to execute a file (i.e., run the file as a program).

To see the permission settings for a file, we can use the ls command. As an example, we will look at the bash program which is located in the /bin

directory:

ls -l /bin/bash

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1113504 Jun 6 2019 /bin/bashHere we can see:

- The file "/bin/bash" is owned by user "root"

- The superuser has the right to read, write, and execute this file

- The file is owned by the group "root"

- Members of the group "root" can also read and execute this file

- Everybody else can read and execute this file

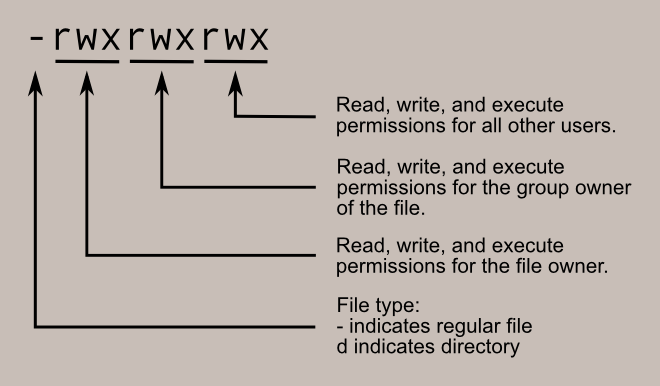

In the diagram below, we see how the first portion of the listing is

interpreted. It consists of a character indicating the file type, followed by

three sets of three characters that convey the reading, writing and execution

permission for the owner, group, and everybody else.

chmod

The chmod command is used to change the

permissions of a file or directory. To use it, we specify the desired

permission settings and the file or files that we wish to modify. There are two

ways to specify the permissions. In this lesson we will focus on one of these,

called the octal notation method.

It is easy to think of the permission settings as a series of bits (which is how the computer thinks about them). Here's how it works:

rwx rwx rwx = 111 111 111 rw- rw- rw- = 110 110 110 rwx --- --- = 111 000 000 and so on... rwx = 111 in binary = 7 rw- = 110 in binary = 6 r-x = 101 in binary = 5 r-- = 100 in binary = 4

Now, if we represent each of the three sets of permissions (owner, group,

and other) as a single digit, we have a pretty convenient way of expressing the

possible permissions settings. For example, if we wanted to set

some_file to have read and write permission for the owner, but

wanted to keep the file private from others, we would:

chmod 600 some_fileHere is a table of numbers that covers all the common settings. The ones

beginning with "7" are used with programs (since they enable execution) and the

rest are for other kinds of files.

| Value | Meaning |

| 777 | (rwxrwxrwx) No restrictions on permissions. Anybody may do anything. Generally not a desirable setting. |

| 755 | (rwxr-xr-x) The file's owner may read, write, and execute the file. All others may read and execute the file. This setting is common for programs that are used by all users. |

| 700 | (rwx------) The file's owner may read, write, and execute the file. Nobody else has any rights. This setting is useful for programs that only the owner may use and must be kept private from others. |

| 666 | (rw-rw-rw-) All users may read and write the file. |

| 644 | (rw-r--r--) The owner may read and write a file, while all others may only read the file. A common setting for data files that everybody may read, but only the owner may change. |

| 600 | (rw-------) The owner may read and write a file. All others have no rights. A common setting for data files that the owner wants to keep private. |

Directory Permissions

The chmod command can also be used to control the

access permissions for directories. Again, we can use the octal notation to set

permissions, but the meaning of the r, w, and x attributes is different:

- r - Allows the contents of the directory to be listed if the x attribute is also set.

- w - Allows files within the directory to be created, deleted, or renamed if the x attribute is also set.

- x - Allows a directory to be entered (i.e.

cd dir).

Here are some useful

settings for directories:

| Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 777 | (rwxrwxrwx) No restrictions on permissions. Anybody may list files, create new files in the directory and delete files in the directory. Generally not a good setting. |

| 755 | (rwxr-xr-x) The directory owner has full access. All others may list the directory, but cannot create files nor delete them. This setting is common for directories that you wish to share with other users. |

| 700 | (rwx------) The directory owner has full access. Nobody else has any rights. This setting is useful for directories that only the owner may use and must be kept private from others. |

Becoming the Superuser for a Short While

It is often necessary to become the superuser to

perform important system administration tasks, but

as we know, we

should not stay logged in as the superuser.

In most distributions, there is a program that can give you

temporary access to the superuser's privileges.

This program is called su

(short for substitute user) and can be used in those

cases when you need to be the superuser for a small

number of tasks. To become the superuser, simply

type the su command. You will

be prompted for the superuser's password:

su

Password:

[root@linuxbox me]#After executing the su command, we have a new

shell session as the superuser. To exit the superuser session, type exit and we will return to your previous session.

In most modern distributions, an alternate method is used. Rather than

using su, these systems employ the sudo command instead. With sudo,

one or more users are granted superuser privileges on an as needed basis. To

execute a command as the superuser, the desired command is simply preceded

with the sudo command. After the command is entered,

the user is prompted for the their own password rather than the superuser's:

sudo some_command

Password for me:

[me@linuxbox me]$In fact, modern distributions don't even set the root account password thus

making it impossible to log in as the root user. A root shell is still possible

with sudo by using the "-i" option:

sudo -i

Password for me:

root@linuxbox:~#Changing File Ownership

We can change the owner of a file by using the chown command. Here's an example: Suppose we wanted to

change the owner of some_file from "me" to "you". We could:

sudo chown you some_fileNotice that in order to change the owner of a file, we must have superuser

privileges. To do this, our example employed the sudo

command to execute chown.

chown works the same way on directories as it does

on files.

Changing Group Ownership

The group ownership of a file or directory may be changed with chgrp. This command is used like this:

chgrp new_group some_fileIn the example above, we changed the group ownership of

some_file from its previous group to "new_group". We must be the

owner of the file or directory to perform a chgrp.

Further Reading

- Chapter 9 of The Linux Command Line covers this topic in much more detail.